Scientists Reconstruct the Oldest Human Face Found in Morocco

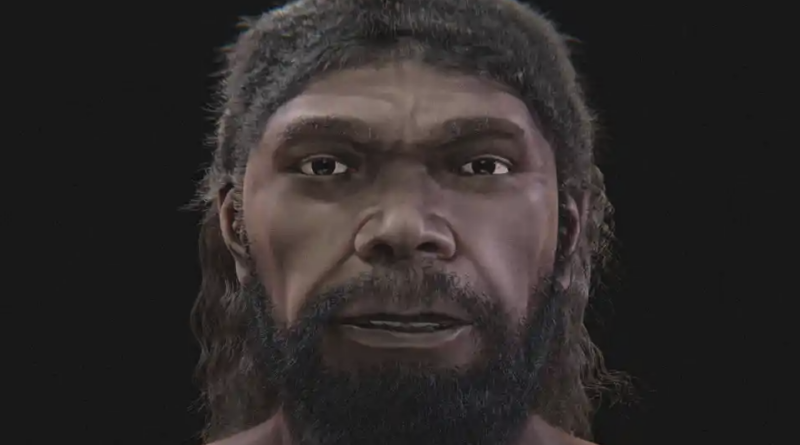

In a breakthrough, scientists have revealed the face of the first Homo sapien, 300,000 years after his death. The oldest known Homo sapien skull, discovered in Morocco, has been digitally reconstructed, unveiling a strong and serene visage that challenges previous timelines of human evolution and migration.

The skull, unearthed at the Jebel Irhoud site in 2017, was missing its lower jaw, but a team led by Brazilian graphics expert Cicero Moraes has meticulously recreated the face. Using data from the Max Planck Institute, Moraes employed a sophisticated process of digital scanning and anatomical deformation to produce the likeness of our ancient ancestor.

Rewriting Human History

The Jebel Irhoud skull’s discovery and subsequent analysis have profound implications for our understanding of human history and major breakthrough in Science. Previously, the oldest known Homo sapiens fossils were found at Omo Kibish in Ethiopia, dated to 195,000 years ago. This led researchers to believe that modern humans descended from a population that lived in East Africa around that time.

However, the Jebel Irhoud remains push the emergence of Homo sapiens back by 100,000 years, suggesting that our species spread across the African continent much earlier than previously thought. Professor Jean-Jacques Hublin, who led the study, explained, “We used to think that there was a cradle of mankind 200,000 years ago in East Africa, but our new data reveal that Homo sapiens spread across the entire African continent around 300,000 years ago. Long before the out-of-Africa dispersal of Homo sapiens, there was dispersal within Africa.”

The Reconstruction Process

The meticulous reconstruction process began with a 3D scan of the skull. Moraes then layered soft tissue and skin onto the digital cranium, drawing from data on modern human anatomy. The final face was an interpolation of this data, creating a detailed and lifelike representation.

“Initially, I scanned the skull in 3D, using data provided by the researchers of the Max Planck Institute,” Moraes explained. “Then I proceeded with the facial approximation, which consisted of crossing several approaches, such as anatomical deformation. This is where the tomography of a modern human is used, adapting it so that the donor’s skull becomes the Jebel Irhoud skull, and the deformation ends up generating a compatible face.”

The donor skull was chosen for its similarity to the ancient skull, allowing researchers to fill in the missing parts. Additional data from modern humans helped predict the thickness of the soft tissue and the likely projection of facial features like the nose. The result was a series of images: one set objective, with technical elements in grayscale, and another artistic, with pigmentation of the skin and hair.

A Glimpse into the Past

The reconstructed face of the Jebel Irhoud skull provides a rare and intimate glimpse into the distant past. Though the true gender of the individual remains unknown due to the absence of pelvic bones, the face presents a powerful image of a strong and serene early human.

Jebel Irhoud has been a significant site for human fossils since the 1960s, with the latest discovery bringing the total number of remains to 22. The team of researchers found skulls, teeth, and long bones from at least five individuals, including two adults and three children, alongside stone tools and animal bones.